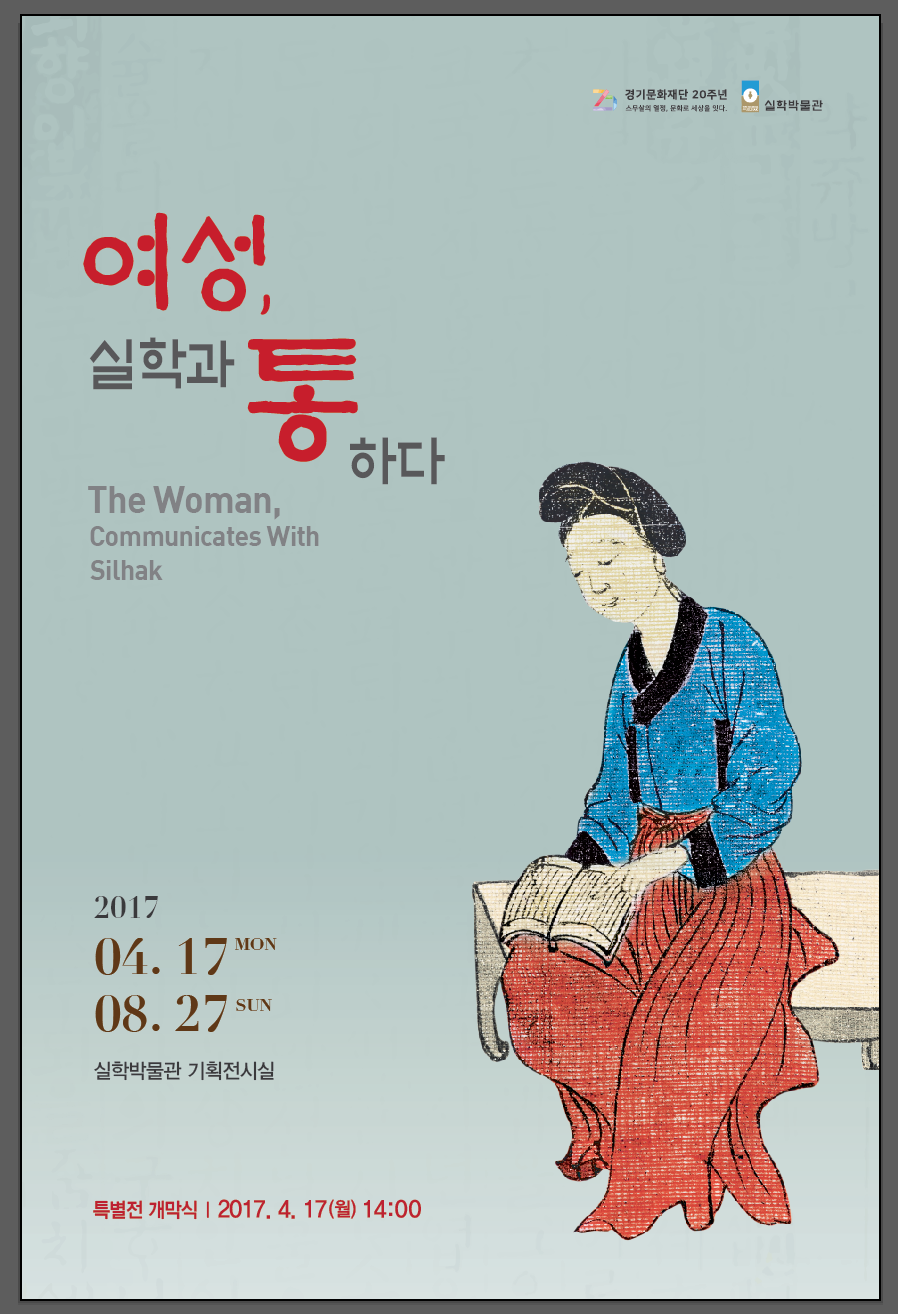

Section 1. Living As a Woman in the Joseon Period

○ Education for Women That Emphasizes Womanly Virtues

In the Joseon period, women read Sohak (Elementary Education) and Samganghaengsildo (Illustrated Conduct of the Three Bonds), and were taught that they should build up womanly virtues, follow the rules as a lady, and keep their place. Women typically received their education from family members, raised so that they could weave, cook, and prepare for ancestral rites. The noble families often kept the Gyenyeoseo (Admonishments for Women), which was used to instruct girls. The most important virtue for women in the Joseon period was to successfully raise children. For example, Jang Gye-hyang (from Andong Jang Clan), who is an acclaimed mother of Joseon, dedicated her life as a daughter, wife, and daughter-in-law. With her son Lee Hyeon-il becoming the Minister of the Board of Personnel, some called her the Lady of Andong Jang, but her full name, Jang Gye-hyang, better fits her. She is not only someone’s mother or wife, but a woman who left behind her own name.

○ Lady Jeong, who Wrote the Biography of her Father-in-law Chae Je-gong

It was unusual in the Joseon Period for a woman to translate the records (in Chinese character) of her father-in-law into Korean so that the women in the family could celebrate him. Lady Jeong, the sister of Dasan Jeong Yak-yong, married Chae Hong-geun, a son by the concubine of the prime minister Chae Je-gong, but unfortunately her husband died within 2 years after their marriage. After becoming a widow at the young age of 19, Lady Jeong kept her chastity, took care of her father-in-law, and collected his records to publish a Korean biography under the title of Sangdeokchongnok, which means ‘to keep the record of the virtues of the prime minister Chae Je-gong’. In the book, you can find his achievements and hidden history of the palace related to Crown Prince Sado.

Section 2. Expressing Oneself with Poems and Studies

○ Writing Poems in the Women’s Quarters

It was hard for a woman to study or learn writing of poems, and even after she had written one by her excellent talent, it was hard for the poem to become known to the outside world. Joseon’s Women were supposed to be confined in the women’s quarters, but there were some women who expressed their inner spirit through poetry. Gigak, an anonymous female poet, Kim Hoyeonjae, and Nam Jeongilheon are most notable, among others.

Although I have the wishes of a man for my entire life

I lament being made to wear the headdress of a mistress

– Gigak

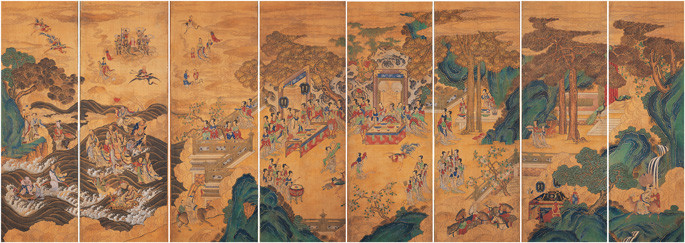

○ Kim Geum-won, who traveled to Geumgangsan Mountain, and Samhojeongsisa

As the social class who enjoyed culture expanded since the 18th century, talented women started to engage in cultural activities. The female culture group Samhojeongsisa is a typical example. Its members include Un-cho, Juk-hyang, Geum-won, who traveled Geumgangsan Mountain disguised as a man, Juk-yeop, the sister of Juk-hyang, who played gayageum skillfully, Geum-hong, an excellent poet, and Gyeong-hye, as well-known as Juk-hyang for her poetry and painting. They all had something in common, in addition to their outstanding artistic talents: they were all either gisaeng or daughters by concubine. Despite their low social status, they brought about a remarkable shift in the cultural landscape in 19th-century Joseon.

Now I understand, however large the sky and the earth

my heart can hold them.

(方知天地大 客得一胸中)

– Hodongseorakgi, Kim Geum-won

○ Birth of Female Silhak Thinkers — A Woman Can Also Become a Noble Sage

There are a number of women who contributed good poems or writings during the Joseon period, but very few studied with the aim of becoming a sage. Im Yunjidang (1721-1793), a female Neo-Confucian scholar, said that there is no difference between men and women in terms of innate nature, that a sage is a normal person like the rest of us, and that everyone can become a sage like Emperor Yao. Gang Jeongildang (1772-1832) was influenced greatly by Im Yunjidang, who had lived in a slightly earlier period, and found the model of a female scholar in Im, empowered by her book. Gang also claimed that there is no difference between men and women in that they have a common good nature, and was confident that women can attain the status of sage if they make the effort to do so.

Section 3. Discourse on Yeollyeo (chaste woman)

○ Discourse on Widows by Yeonam Park Ji-won and Dasan Jeong Yak-yong

Widows are those women who live lonely, in a deep sorrow. In the introduction of Yeollyeo hamyang bakssijeon (Biography of Yeollyeo from Hamyang Park Clan) by Park Ji-won, an old widow shows a coin, worn away at the edge from rolling whenever she failed to fall asleep, to her son. The author says that this old widow, who has kept her chastity for decades, is indeed a yeollyeo. In the Joseon Period, however, so many women kept their chastity that, apart from cases where women took their own lives, they were generally unknown.

Park Ji-won wrote three biographies of yeollyeo during his lifetime. In his second work, he describes vividly the anguish of a woman who is hesitating in the face of death. He writes it with the intent of revealing the agony of a yeollyeo. The book was on one hand a study of the custom of yeollyeo, while also a critique of it.

Park’s third biography of yeollyeo is the Biography of Yeollyeo from Hamyang Park Clan, one that he wrote in 1796 at the age of 57 while working as a County Magistrate of Anui. In this book, he delivers a full account of a yeollyeo from the Hamyang Park Clan, who took her own life by taking a drug after giving a third-year memorial service for her husband’s death. The author praises her as yeollyeo, but at the same time, he is considerate of the circumstances which led her to death.

It was not only Park Ji-won who felt doubts about the cruel culture of killing oneself. Dasan Jeong Yak-yong’s criticism offered a piercing reproach to the futile suicide custom of women who followed their husband in death.

“Suicide is one of the most disgraceful acts in the world; however, the ruling class exempts corvée labor from the village members of those who committed suicide and reduces the compulsory labor for their sons or grandsons. This encourages the people regarding the most disgraceful thing in the world. How can it be called righteous?”

– Dasan Jeong Yak-yong

○ A Confession of Lady Jo from Pungyang Clan, who Failed to Become Yeollyeo

The women who followed their husband in death were praised as yeollyeo, but not all widows took their own life after their husband. In the late 18th century, Lady Jo from Pungyang Clan (1772-1815) agonized between life and death, with guilt, after her husband died before her, six years after their marriage. She decided to live on after the persuasion of her father and her mother-in-law, and made a confession of her innermost feelings after 20 years in her autobiography. She did not hide the distress that she had suffered because she could not be a yeollyeo after her husband’s death.

“I could not die with the thought of becoming unfilial and making another tragedy occur. Suddenly, I changed my mind to live on and accept my harsh destiny, rather than adding to the sorrow of my parents and parents-in-law.”

– Autobiography

Section 4. Birth of Woman Silhak Thinker

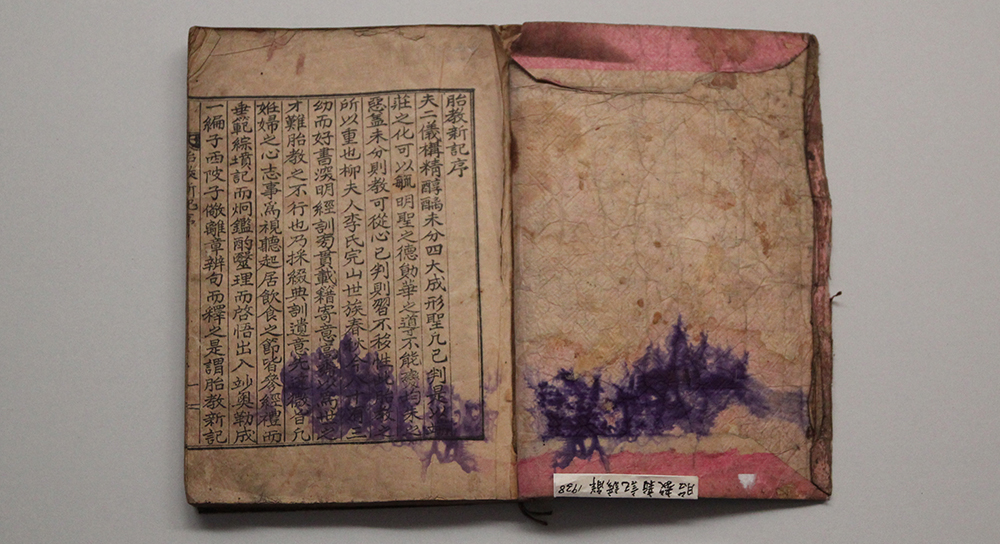

○ Lee Sajudang, Writing a Book on Prenatal Education, the First in the World

In the Joseon Period, people were mostly interested in the baby’s gender rather than other issues of pregnancy. Giving birth to a son and making him succeed the family’s pedigree held that much significance. However, there was someone who was interested in the prenatal education of a fetus, rather than its gender—Lee Sajudang (李師朱堂, 1739-1821). Her son is Yu-hui (柳僖), a silhak scholar and linguist who left more than a hundred books, including Eonmunji (Monograph on Korean). In 1800, Lee Sajudang published Taegyosingi (New Records for Prenatal Care), written in Chinese letters. Her age was 62 when writing the book. In Taegyosingi, she put emphasis not only on the behaviors of the wife, but also those of the husband. It broke the common notion that prenatal education is all about women. In 1801, Yu-hui rearranged her book into ten sections and annotated it, republishing it in a Korean version. Today’s Taegyosingi is this revised edition by Yu-hui.

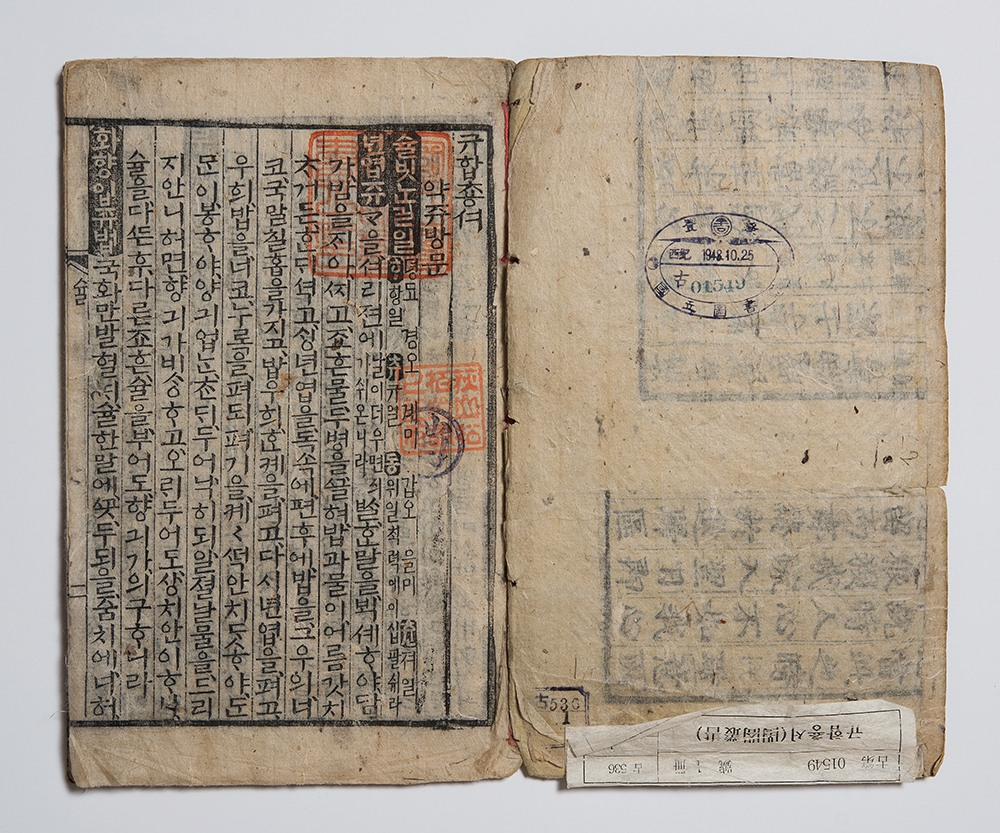

○ Lee Bingheogak, Writing about Women’s Lifestyle Economy

Lee Bingheogak (李憑虛閣, 1759-1824), a female silhak scholar, was from a noble family. She was married at the age of 15 to Seo Yu-bon (徐有本, 1762-1822), who was three years younger than her. Seo’s father was Seo Ho-su, a silhak scholar, and Seo’s brother is Seo Yu-gu, the author of Imwongyeongjeji (Book of Forestry Economy). Lee Sajudang, the author of Taegyosingi, is Lee’s maternal aunt.

Bingheogak completed compiling the Gyuhapchongseo (Composite Guide for the Inner Quarters) in 1809, at the age of 51. Gyuhap means the woman or the place where women stay. Gyuhapchongseo can be understood as an encyclopedia on household arts. The investigation on the food, clothing, and shelter was not the exclusive property of women. Silhak scholars studied them in depth as they extended their field of study, from Neo-Confucian metaphysics to practical thinking.

The knowledge that is compiled in Gyuhapchongseo by Lee Bingheogak shows the new trends of study in the late Joseon period. Lee wrote it in Korean and made citations of more than 80 books included. Gyuhapchongseo was known to her relatives and transcribed while she was living, and continued to be transcribed after her death to become the most widely read among books on household arts published in the late 19th century.

Contents of Gyuhapchongseo

① Jusaui – making liquors and dishes

② Bongimcheuk – making clothing, dyeing, weaving, embroidering, silk-farming

③ Sangarak – farming, planting flowers, raising livestock

④ Cheongnanggyeol – prenatal education, infant care, first aid

⑤ Sulsuryak – choosing auspicious directions, fortune telling, talismans, casting out demons, disaster prevention